International Resource Centre

New Afghanistan law to silence victims of violence against women

A new Afghan law will allow men to attack their wives, children and sisters without fear of judicial punishment, undoing years of slow progress in tackling violence in a country blighted by so-called “honour” killings, forced marriage and vicious domestic abuse.

The small but significant change to Afghanistan’s criminal prosecution code bans relatives of an accused person from testifying against them. Most violence against women in Afghanistan is within the family, so the law – passed by parliament but awaiting the signature of the president, Hamid Karzai – will effectively silence victims as well as most potential witnesses to their suffering.

“It is a travesty this is happening,” said Manizha Naderi, director of the charity and campaign group Women for Afghan Women. “It will make it impossible to prosecute cases of violence against women … The most vulnerable people won’t get justice now.”

Under the new law, prosecutors could never come to court with cases like that of Sahar Gul, a child bride whose in-laws chained her in a basement and starved, burned and whipped her when she refused to work as a prostitute for them. Women like 31-year-old Sitara, whose nose and lips were sliced off by her husband at the end of last year, could never take the stand against their attackers.

“Honour” killings by fathers and brothers who disapprove of a woman’s behaviour would be almost impossible to punish. Forced marriage and the sale or trading of daughters to end feuds or settle debt would also be largely beyond the control of the law in a country where the prosecution of abuse is already rare.

Sahar Gul’s in-laws chained her in a basement and starved, burned and whipped her when she refused to work as a prostitute for them.

Photograph: Kuni Takahashi/New York Times/ Redux/eyevine

It is common in western legal systems to excuse people from testimony that might incriminate their spouse. But it is a very narrow exception, with little resemblance to the blanket ban planned in Afghanistan.

Human Rights Watch said it would “let batterers of women and girls off the hook”.

The change is in a section of the criminal code titled “Prohibition of Questioning an Individual as a Witness”. Others covered by the ban are children, doctors and defence lawyers for the accused.

Senators originally wanted a milder version of the law that would prevent relatives from being legally obliged to take the stand in a case in which they did not want to testify.

But both houses of parliament eventually passed a draft banning all testimony.

As most Afghans live in walled compounds, shared only with their extended families, this covers most witnesses to violence in the home.

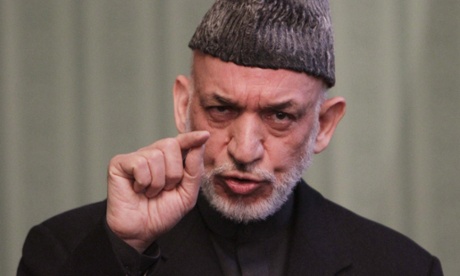

Hamid Karzai has presided over a strengthening of conservative forces in Afghanistan.

Photograph: S Sabawoon/EPA

The bill has been sent to Karzai, who must decide whether to sign it into force. After failing to block the change in parliament, campaigners plan to throw their weight behind shaming the president into suspending the new law.

“We will ask the president not to sign until the article is changed, we will put a lot of pressure on him,” said Selay Ghaffar, director of the shelter and advocacy group Humanitarian Assistance for the Women and Children of Afghanistan. She said activists hoped to repeat the success of a campaign in 2009 that forced Karzai to soften a family law enshrining marital rape as a husband’s right.

But that was five years ago, and since then Karzai has presided over a strengthening of conservative forces. In the last year alone parliament has blocked a law to curb violence against women and cut the quota for women on provincial councils, while the justice ministry floated a proposal to bring back stoning as a punishment for adultery.

“In the beginning they were a little scared with the new government and media,” Ghaffar said, referring to the period soon after the Taliban’s fall when women’s rights were a focus of international attention. “Now they do whatever they want as they have seen the government is not very democratic or strongly in favour of women’s rights.”

Foreign troops are heading home in large numbers and will all be gone by the end of the year. A long-term deal to keep US forces on in small numbers to train Afghan soldiers and chase international militants along the Pakistani border is failing as a result of opposition from Karzai.

Ties with Washington, which have been bad for years, have worsened amid tensions over the deal, the release of dozens of prisoners who the US says are dangerous Taliban members, and feuding over insurgent attacks and civilian casualties.

Countries that spent billions trying to improve justice and human rights are now focused largely on security, and are retreating from Afghan politics.

Heather Barr, Afghanistan researcher with Human Rights Watch, said: “Opponents of women’s rights have been emboldened in the last year. They can see an opportunity right now to begin reversing women’s rights – no need to wait for 2015. The lack of response from donors has energised them further. Everyone has known since May that this law could be passed but we didn’t hear any donors speaking out about it publicly.”

A link to the article can be found here.

Mar